Social media presents its own problems with sharing content and the modern day blogger has become a slave to algorithms. For example Facebook prevent you from reaching your own audience unless you’re willing to boost posts, which in effect is paying to advertise posts to reach people you’ve already connected with.

With the start of a new year what I’m looking to do is to set up a mailing list, so if you’d like to receive a monthly letter from the site feel free to drop me a mail at [email protected] or hit the subscribe button.

This is a shortened version of a very interesting article taken from washingtonmonthly, written by Roger McNamee (@Moonalice) originally titled How to Fix Facebook – Before it Fixes Us

In my thirty-five-year career in technology investing, I have never made a bigger contribution to a company’s success than I made at Facebook. It was my proudest accomplishment. Not surprisingly, Facebook became my favorite app. I checked it constantly, and I became an expert in using the platform by marketing my rock band, Moonalice, through a Facebook page.

Facebook, Google, and other social media platforms make their money from advertising. As with all ad-supported businesses, that means advertisers are the true customers, while audience members are the product. Until the past decade, media platforms were locked into a one-size-fits-all broadcast model. Success with advertisers depended on producing content that would appeal to the largest possible audience.

Whenever you log into Facebook, there are millions of posts the platform could show you. The key to its business model is the use of algorithms, driven by individual user data, to show you stuff you’re more likely to react to.

Algorithms that maximize attention give an advantage to negative messages. The result is that the algorithms favor sensational content over substance.

It took Brexit for me to begin to see the danger of this dynamic. I’m no expert on British politics, but it seemed likely that Facebook might have had a big impact on the vote because one side’s message was perfect for the algorithms and the other’s wasn’t.

The “Leave” campaign made an absurd promise—there would be savings from leaving the European Union that would fund a big improvement in the National Health System—while also exploiting xenophobia by casting Brexit as the best way to protect English culture and jobs from immigrants. It was too-good-to-be-true nonsense mixed with fearmongering.

Meanwhile, the Remain campaign was making an appeal to reason. Leave’s crude, emotional message would have been turbocharged by sharing far more than Remain’s.

I did not see it at the time, but the users most likely to respond to Leave’s messages were probably less wealthy and therefore cheaper for the advertiser to target: the price of Facebook (and Google) ads is determined by auction, and the cost of targeting more upscale consumers gets bid up higher by actual businesses trying to sell them things.

As a consequence, Facebook was a much cheaper and more effective platform for Leave in terms of cost per user reached. And filter bubbles would ensure that people on the Leave side would rarely have their questionable beliefs challenged. Facebook’s model may have had the power to reshape an entire continent.

The most important tool used by Facebook and Google to hold user attention is filter bubbles. The use of algorithms to give consumers “what they want” leads to an unending stream of posts that confirm each user’s existing beliefs.

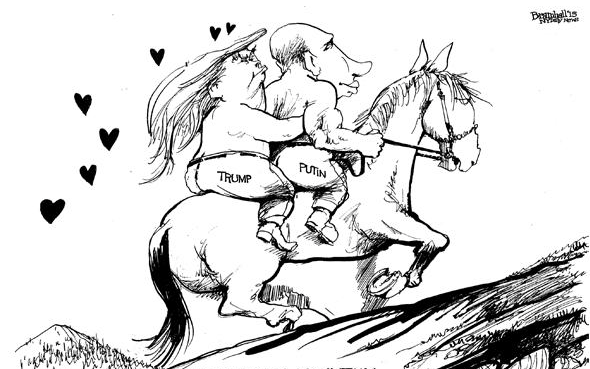

We now know, for instance, that the Russians indeed exploited topics like Black Lives Matter and white nativism to promote fear and distrust, and that this had the benefit of laying the groundwork for the most divisive presidential candidate in history, Donald Trump. The Russians appear to have invested heavily in weakening the candidacy of Hillary Clinton during the Democratic primary by promoting emotionally charged content to supporters of Bernie Sanders and Jill Stein, as well as to likely Clinton supporters who might be discouraged from voting.

Once the nominations were set, the Russians continued to undermine Clinton with social media targeted at likely Democratic voters. We also have evidence now that Russia used its social media tactics to manipulate the Brexit vote. A team of researchers reported in November, for instance, that more than 150,000 Russian-language Twitter accounts posted pro-Leave messages in the run-up to the referendum.

We hypothesize that the Russians were able to manipulate tens of millions of American voters for a sum less than it would take to buy an F-35 fighter jet.

In the case of Facebook and Google, the algorithms have flaws that are increasingly obvious and dangerous.

Thanks to government’s laissez-faire approach to regulation, the internet platforms were able to pursue business strategies that would not have been allowed in prior decades. No one stopped them from using free products to centralize the internet and then replace its core functions. No one stopped them from siphoning off the profits of content creators. No one stopped them from gathering data on every aspect of every user’s internet life. No one stopped them from amassing market share not seen since the days of Standard Oil. No one stopped them from running massive social and psychological experiments on their users. No one demanded that they police their platforms. It has been a sweet deal.

Facebook and Google are now so large that traditional tools of regulation may no longer be effective. The European Union challenged Google’s shopping price comparison engine on antitrust grounds, citing unfair use of Google’s search and AdWords data. The harm was clear: most of Google’s European competitors in the category suffered crippling losses. The most successful survivor lost 80 percent of its market share in one year. The EU won a record $2.7 billion judgment—which Google is appealing.

Unfortunately, there is no regulatory silver bullet. The scope of the problem requires a multi-pronged approach.

First, we must address the resistance to facts created by filter bubbles. Polls suggest that about a third of Americans believe that Russian interference is fake news, despite unanimous agreement to the contrary by the country’s intelligence agencies. Helping those people accept the truth is a priority. I recommend that Facebook, Google, Twitter, and others be required to contact each person touched by Russian content with a personal message that says, “You, and we, were manipulated by the Russians. This really happened, and here is the evidence.” The message would include every Russian message the user received.

This idea, which originated with my colleague Tristan Harris, is based on experience with cults. When you want to deprogram a cult member, it is really important that the call to action come from another member of the cult, ideally the leader.

Second, the chief executive officers of Facebook, Google, Twitter, and others—not just their lawyers—must testify before congressional committees in open session. Forcing tech CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg to justify the unjustifiable, in public—without the shield of spokespeople or PR spin—would go a long way to puncturing their carefully preserved cults of personality in the eyes of their employees.

We also need regulatory fixes. Here are a few ideas.

First, it’s essential to ban digital bots that impersonate humans.

Second, the platforms should not be allowed to make any acquisitions until they have addressed the damage caused to date, taken steps to prevent harm in the future, and demonstrated that such acquisitions will not result in diminished competition.

Third, the platforms must be transparent about who is behind political and issues-based communication. The Honest Ads Act is a good start

Fourth, the platforms must be more transparent about their algorithms. Users deserve to know why they see what they see in their news feeds and search results. Consumers should also be able to see what attributes are causing advertisers to target them.

Fifth, the platforms should be required to have a more equitable contractual relationship with users. Facebook, Google, and others have asserted unprecedented rights with respect to end-user license agreements (EULAs). If there are terms you choose not to accept, your only alternative is to abandon use of the product. For Facebook, where users have contributed 100 percent of the content, this non-option is particularly problematic. All software platforms should be required to offer a legitimate opt-out, one that enables users to stick with the prior version if they do not like the new EULA.

Sixth, we need a limit on the commercial exploitation of consumer data by internet platforms. Customers understand that their “free” use of platforms like Facebook and Google gives the platforms license to exploit personal data. The problem is that platforms are using that data in ways consumers do not understand, and might not accept if they did.

Seventh, consumers, not the platforms, should own their own data.

The Full article is a much longer read but enjoyable:

https://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/january-february-march-2018/how-to-fix-facebook-before-it-fixes-us/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed