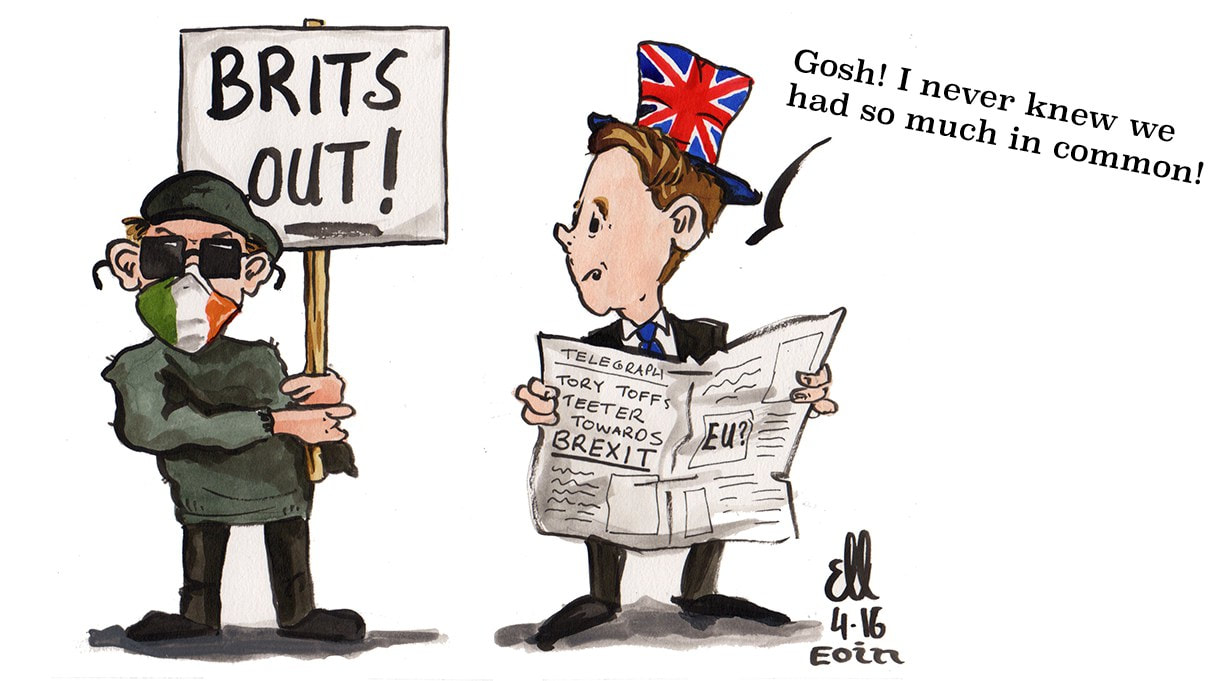

The post has deep roots in identity politics and nationalist thinking. It’s a grandchild of the cultural revolution, a period of self awareness which taught us to be proud of our country and unique identity. Originally titled Britain and Ireland: Neighbours and Frenemies, it’s a stretch further than most the posts I share but I would like to encourage everyone to connect with that source of identity which Jason is tapping back into. It’s worth a read in its entirety as it captures some of the border tension around the Brexit negotiations which have just about dominated the Irish news lately.

What’s with all this talk of friendship between Britain and Ireland?

No such friendship exists and nor has it ever existed.

This is nothing but cold toleration and even that is getting close to ending.

Late last month Fintan O’Toole, one of Ireland’s foremost political commentators, published an article in The Irish Times headed: “The hard-won kinship between Britain and Ireland is threatened by Brexit idiocy.” In this he describes how Ireland, “Britain’s best friend on the other side of the negotiating table,” is being forced by the British government’s inaction and “sheer incompetence” to distance itself from a neighbour with which, through the peace process, it has “developed a genuine trust.” Reading this on the morning it was published I laughed out loud imagining everyone else in the country reading it and spitting their tea all over the breakfast table.

Small islands, as the saying goes, have long memories.

In Ireland there is a well-worn proverb relating to the Irish people’s relationship to England, and it is as apt today as ever it was. “Beware,” it runs, “of the hoof of the horse, the horn of the bull, and the smile of the Saxon.” There is no trust of Britain on the island of Ireland. Not even the so-called loyalists in the occupied counties in the north trust a word that comes from the mouth of the British government. This is simply a reality of the Irish experience, and one that has only been reinforced by Brexit.

No doubt Fintan was being diplomatic. After all, he does write for a constituency of the Irish population – The Irish Times readership – that still does business with England. At times we all have to moderate our tones, but this business of a kinship or affinity between the Irish and the “Brits” – hard-won or otherwise – is absolute hokum. Britain – a large portion of the media conditioned population and the ruling establishment in its entirety – detests Ireland, and Ireland – after 900 years of brutal colonial occupation – will never trust England. What these two countries have is a working relationship, one that works pretty well considering their long historical entanglements.

During the years of plenty; the years following the signing of the Good Friday Agreement and the time of Ireland’s economic boom, things were looking good for Anglo-Irish relations. The hatchet wasn’t exactly buried, but at least no one was eager to mention the war.

In February 2007, during the renovations of Lansdowne Road, the English rugby squad played Ireland in the Six Nations at the Gaelic ground Croke Park in Dublin – where on 21 November 1920, during the War of Independence, British Auxiliaries opened fire into the crowd, killing eleven civilians and wounding over sixty. Few who had come to support England that day would have realised the significance and the massive concession being made as God Save the Queen was played.

In mid-May 2011 Elizabeth Saxe-Coburg und Gotha became the first reigning British monarch to visit Ireland since 1911. She laid a wreath at the Garden of Remembrance, the place where Ireland remembers those who laid down their lives for the freedom of their country. Of course she did this “for all who died,” remembering even those who came to Ireland to torture and kill as occupiers, before attending a state banquet at Dublin Castle – the centre of the British administration until 1922.

Marking the one hundredth anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising the Irish government made the controversial decision to put the names of the British soldiers killed in the rising next to the Irish who fell in their effort to expel them. Where, we must ask, on the cenotaph in London or on any British war memorial are the names of Irish Republican volunteers from 1916 to 1997 who were killed fighting for their country against Britain?

The point is that at every step of the way on this long journey towards peace and reconciliation between these two countries Ireland has made all the concessions, and the Irish people have done this with remarkable patience.

Now that Ireland has shown itself to be a proper state in Europe with enough clout in the European Union to defend itself from yet another round of British aggression – and that’s what the border question is – the British are once again ramping up the anti-Irish sentiment.

Irish citizens live under British occupation in “Northern Ireland” and Ireland has the right to protect them. Yet because this poses a threat to Britain’s plans – Britain’s plans in Ireland – we have English MPs like Owen Paterson describing it as “blackmail,” UKIP’s Gerard Batten talking about the UK being “threatened” by a “tiny country,” and Kate Hoey insisting Trump-like that Ireland should be made to pay for any hard border that might be imposed on Ireland.

Trust? Kinship? Not likely. Britain is the same old heart-scald it has always been to Ireland. Nothing has changed. This should be a lesson to Scotland and Wales. If people think the English state is the geopolitical equivalent of a bout of haemorrhoids while they’re trying to free themselves from it, they should consider how those who have already beaten it are treated.

This lingering, cancerous British contempt for Ireland even comes down to the way Ireland is spoken of in the British press, and this drives Ireland demented. Where the hell is this “southern Ireland?” Southern Ireland is places like Limerick, Waterford, and Cork, much like Bristol, Southampton, and London are in southern England. There is no “southern Ireland.”

Southern Ireland is not, as these idiots like to think, the opposite of “Northern Ireland.” The opposite of Northern Ireland is a free and undivided Ireland – a united Ireland. That’s the opposite of Northern Ireland.

Even Northern Ireland isn’t northern Ireland. The most northerly county in Ireland is Donegal, and it would come as a serious shock to the fine people of Buncrana, Letterkenny, and Donegal town to discover they were back under British rule.

Sometimes we even here them refer to “Ulster” as though this is a synonym for this “Northern Ireland.” Ulster – or Uladh – is one of four provinces of Ireland, the others being Leinster, Connaught, and Munster. Ulster has nine counties; six currently under effective direct rule from London and three – Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan – are not.

The “Republic of Ireland” is a little better, but still annoying. No one calls Britain the Constitutional Monarchy of Britain. Article 4 of An Bunreacht na hÉireann – the Constitution of Ireland – reads simply: “The name of the State is Éire, or, in the English language, Ireland.” Republic of… is merely the form of government it has, and this, as Article 1 of the Constitution affirms is subject to change. So there you have it. Ireland is Ireland.

Since Brexit began to take shape, and certainly from the moment it began to dawn on the British government that Ireland would be instrumental in shaping it, the scab has been picked and opened; revealing that the hard-won kinship and mutual trust and respect was all a load of tosh.

Britain cannot abide not having its own way, and when anything or anyone gets in its way we are all back to square one with the ages-old rhetoric of hate and empire. Still, these are happy times for Ireland and all who look forward to a stress free future.

Brexit is all about making Britain exceptional, and it will be. It will soon become the only state in the modern world to have propelled itself into non-existence. Republican prisoner Bobby Sands (an MP until he died in a British prison) used the Irish term Tiocfaidh ár lá – “Our day will come” – when he wrote of his hopes for the future of Ireland. Well Bobby, your day has come.

(Picture by @EoinKr)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed