The “safety pin movement” began in the wake of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union. Amid reports of post-Brexit hate crimes, an American living in London posted now-deleted tweets urging people to wear safety pins on their outer garments to show their willingness to protect people being abused. Within days, the hashtag #safetypin was trending on Twitter. The campaign caught on quickly in the United States after Trump won.

“This is meant to be more than just a symbolic gesture or a way for like-minded people to pat each other on the back. If people wear the pin and support the campaign they are saying they are prepared to be part of the solution. It could be by confronting racist behaviour, or if that is not possible at least documenting it. More generally it is about reaching out to people and letting them know they are safe and welcome.” @Cheeah (Campaign Founder)

“I won’t trust anyone just because they are wearing a safety pin. No, it won’t give me any comfort. I will trust actions, nothing more, nothing less. I wear my blackness every single day, and people don’t have to look for it to target me. Don’t make me look for your symbol of support. Show it every day in your words and deeds. Yes, it’s nice to tell marginalized populations that you won’t hurt them, but it’s even nicer to make sure that sexist White Supremacists know that they are not safe attacking me.” @IjeomaOluo Ijeoma Oluo, named one of the Most Influential People in Seattle by Seattle Magazine.

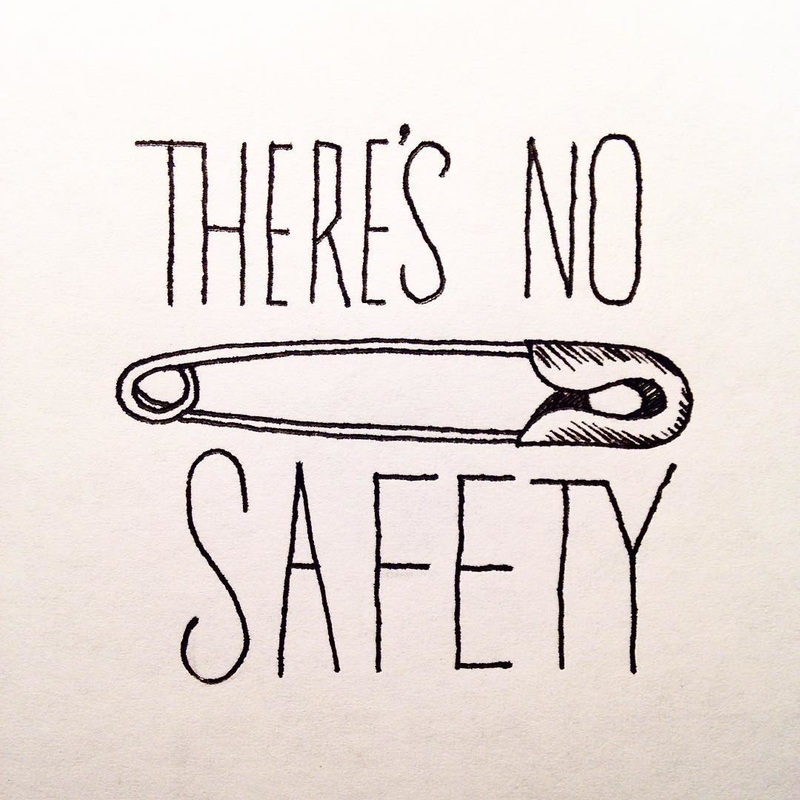

“A safety pin is literally one of the most insignificant things one could wear. They are nothing but badges made for white people to assuage white guilt and declare themselves allies completely autonomously. It's convenient and puts the wearer under absolutely no scrutiny from their peers. It signifies almost nothing at all. It is a self-administered pat on the back for being a decent human being. Privilege at its finest.” @MajorPhilebrity Phillip Henry is an actor, comedian, & singer

“The act is meant to show solidarity with women, Muslims, minorities, the LGBT community, and anyone else who fears what this new nativist chapter may mean for their safety and well-being.” @mgustashaw Megan Gustashaw Contributing Fashion Editor at GQ

“When I’m sitting on a train and I see your safety pin, I don’t think: ‘Hurrah, now I feel safe.’ My default expectation from you as a human being in society is to not be racist or call me a Paki on my morning commute. Wearing a safety pin just reminds me that I’m not safe, and telling me that you’re on ‘my side’ just reinforces the idea of sides. I don’t want sides. I want to go to work, do my job, go to the pub and not have to wear my race on my sleeve while doing it.” @HuffPostPoorna Poorna Bell Executive Editor, The Huffington Post UK

“This really does nothing to dismantle racism/White Supremacy — You’re not a special snowflake.” @cjwilburn Courtney Wilburn, blogger from Philadelphia

“I know, I know, you’re uncomfortable. You feel guilty. You think people are going to suspect you of being a racist, and you want some way to assuage that guilt and reassure your neighbors that you’re one of the good ones. But you know what? You don’t get to do that. You need to sit in your guilt right now. You need to feel bad. So do I, so do all of us. We fucked up. We didn’t do enough to change the minds of our fellow White people” @keeltyc Christopher Keelty blogger from New York

RSS Feed

RSS Feed