Statues and monuments all across Ireland tell different stories from different time periods, which highlight the diversity and complexity of our journey through the ages.

Internationally there has been an energetic movement to challenge some of the more embarrassing elements of the past, with petitions to remove confederate statues from public parks in America closely correlated with a statue of slave owner Edward Colston taking a swim in Bristol.

The recent wave of mob justice over racist landmarks has stirred up a bit of fervour in Ireland too, with calls to remove some conspicuous, but perhaps misplaced sculptures, we face the possibility of erasing our history at the whim of a purist ideology which deems no statue should court controversy. In ancient times the practice of erasing someone from history was considered a fate worse than death, akin to being cast into oblivion. One of the most famous examples is that of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten who around 1353BC tried to convert his people to believe in one god, the sun god Aten. Some historians have made links between Akhenaten and the biblical character Moses, as he lead his followers out of Egypt and into the desert to start a new kingdom. On his death not only did his followers return to their old gods but the new pharaoh (Tutankhamun) had any record of his name or presence destroyed, to the extent that he wasn’t rediscovered until the late 19th century, and the history of ancient Egypt had to be completely rewritten.

Erasing the past does not serve the same purpose as removing statues or symbols of hate that cause mass offence to a great number of people. As such it’s important that we are able to tolerate and respect the opinions of different groups in a shared society. This often means respecting monuments that we might not necessarily agree with. So here’s a little bit of info about the most controversial statues in Ireland and why we should keep them.

Following Ireland’s first true milestone in independence an unavoidable feud erupted which resulted in a violent civil war, the fallout of which resonated for many years. For some the hurt and bloodshed was never forgotten, which is why men like Seán Russell found themselves securing arms from the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany many years later.

The statue of Seán Russell in Fairview has been attacked several times, on the premise that he was a terrorist Nazi sympathiser who died on board a u-boat in 1940.

However the statue remains an important example of how Ireland’s history is far from a linear path; Seán Russell fought in the 1916 rising, the war of independence, and was so anti treaty that he favoured firearms over democracy till the day he died. His belief in continuing a forgotten war is a tragedy that repeated itself in Republican fanaticism for many decades more.

However it’s unfair to call him a Nazi or a Nazi sympathiser as in no way did he further the cause of Nazi Germany or align with their bigotry. In fact at the time Russell’s IRA were busy kicking fascist blue shirts and were closely linked to Fianna Fail until De Valera started to sever ties to maintain peace with the UK, under the guise that Ireland was to remain a neutral country during the European conflict.

The statue is a reminder that 1920 was not an easy struggle, that bloodshed is humanity lost, that bitterness lasts for many years. It remains in place as reminder that military action by Irish Republicans continued for longer than most people are comfortable with, and that finding peace was as big a task as winning independence.

Yes this funny shaped block is number two on the list. In 2020 PBP Galway called for the removal of a sculpture gifted to Galway by the city of Genoa in 1992. The sculpture plays on loose historical records that Christopher Columbus visited Galway in 1477.

The ultra left wing group have taken offence to the genocidal colonisation of the New World by Columbus in 1492, his racial views of the indigenous people, and his contribution to the international slave trade of the time.

The danger of holding 15th century explorers to the ideals of 21st century morality is that we would end up tearing down everything we own. Christianity in the middle ages is immersed in war, atrocity, and conquest. Of course PBP would just as likely remove all aspects of Christianity from public life, it’s as easy for them to remove an artistic monument about exploration as it is to remove statues of the virgin Mary from grottoes all over Ireland.

The argument that Galway Merchants were responsible for the slave trade is the same as blaming County Clare for the Iraq war, it’s meaningless to suggest a city/county without prosperous means is a participant in the acts of superpowers who bully their way through Ireland. Calling for its removal furthers the belief of conservatives that the far left are intolerant and a danger to their way of life. As such calling for its removal is premature given the debate on how we view conquistadors has only begun.

The monument itself has more to do with Ireland’s links with Europe, Galway’s historic ties with Italy and Spain, as well as the Irish desire for freedom & exploration. It was a gift to the city and it is a popular tourist attraction, serving more purpose near the Spanish Arch than in the quiet halls of a museum.

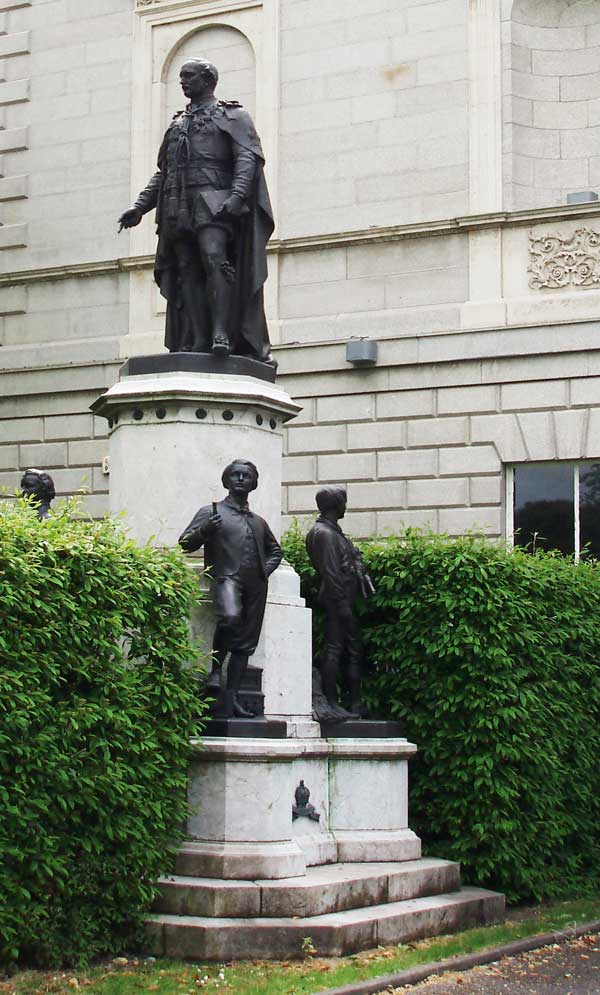

Outside the Dail stands Prince Albert, husband to the Famine Queen and one of the last prominent statues of the British Empire in Ireland. A lot of people get upset at the thought of our former colonial masters trolloping around in the gardens outside the Oireachtas, and it’s certainly ironic considering we fought for a Republic to be independent of the rule of monarch and empire.

However the statue of Albert is a national treasure, sculpted by Irish artist John Henry Foley who also created the towering statue of Daniel O’Connell on O’Connell street. Again another example of how differences of opinion are very closely related in Irish history. In fact there was another Foley statue of Queen Victoria in Dublin, but this was removed for safe keeping in 1949 and gifted to Australia in 1987, where people hold her in higher esteem.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Ireland at the height of the famine in 1849, history has not been kind to England’s handling of famine relief but at the time Victoria was welcomed with banners that read “Hail Victoria, Ireland's hope and England's glory”, and the people of Cork renamed Cobh as Queenstown after her visit. Its note worthy that despite the politics of the empire, and the conflict of war, there was no animosity for the royal visit at the time. So we should not be so quick to erase our history and the details of our relationship with Prince Albert.

Aside from the starvation of our people at the hands of the empire, it’s worth looking at Prince Albert and judging him by some of his actions. He was considered to have very liberal views, unlike other landowners of the time he opposed child labour and supported moves to raise the legal working age. He’s also known for his contribution to the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, making slavery illegal throughout the empire.

Now try imagine what city life was like in the late 19th century, and that the progress of worker’s rights was often as a result of handouts from the ruling class of the time. Prince Albert seems to be a man of good conscious, as president of the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes he championed better housing conditions for the poor. This is no small feat either, especially given the narrative that landlords were very cruel to Irish tenants.

So again it’s not clear that the statue of Prince Albert is grossly offensive, it’s a reminder of the past and the struggles for progress of human rights. It’s hard to say where statues are best placed but I also think there is little point in housing them all in a museum or gifting them to Queensland.

Personally I like touring around a city when I visit, and discovering different aspects of history at every location. It would be a shame to lose our rich and diverse range of monuments to appease a small group who show little tolerance to the stepping stones that lead us on the journey through our past, not all of which may be entirely glorious but none of which is profoundly grotesque.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed